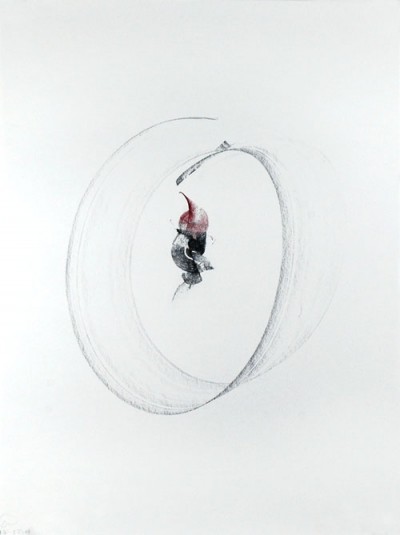

axial drawing

~~~

~~~

~~~

~~~

~~~

[album=1,compact]

~~~

~~~

~~~

~~~

Axial art in this usage stands for visual art created according to an axial principle. In the case of axial drawing, the practice involves drawing from the lower center of the body, rather than from the arm or wrist. In virtually all of the work since 2006 it also involves drawing with two hands simultaneously, where each of the hands is part of a core movement yet is an independent expression of that movement. The term axis is quite literal in that it refers to the axis around which movement occurs. That movement is free of design intention in that no particular outcome is envisioned, yet it is not free of another level of intention that arises performatively inside the actual impulse to draw at a particular time and with specific materials. Where the drawing “comes from” or “whose intention is expressed” are pretty much unanswerable in that the questions are malformed for the particular phenomenon. The question of intention invites another approach rooted in the experience of either making the drawing or viewing it. Each drawing is a signature of a particular emergence. How one interprets this depends on the tendencies of one’s own thinking. This artist makes no particular claim as to whether, for instance, the drawing expresses my own unconscious (I feel quite conscious when making it) or channels another entity (no entities have identified themselves so far) or is “automatic” in the Surrealist sense (I don’t feel surreal but perhaps hyperreal––and in any case automaticity is not a clear cover story for the variety of practices even among historical Surrealists). The drawing is axial which also means that the interpretation is axial––free to move into further configurative understanding in each viewing and inquiry. The axial invites an unprogrammed and unprogrammable yet intensely focused state of mind open to further configuration as insight into our further nature.

~~~

The question of artist merit or accomplishment is a vexed one art-historically. Pollock eventually won approval, perhaps in part because of Clement Greenberg’s imprimatur, but also, it seems, because it is said that he wasn’t only dripping paint (it wasn’t just chance), he was also drawing. Of course this begs the question of what drawing is. What about Michaux? What about Cage’s “drawings”? And, perhaps even more interesting, what about the work of Aboriginal artist Emily Kame Kngwarreye? She began painting at age 70 and did most of her works (in the thousands) between age 80 and 86––and about whom more than one critic has said, she’s greater than Pollock! I have no particular interest in entering this discussion or expressing an opinion. For me the only thing more mysterious than the origin of the work is why I like one drawing more than another; I definitely do; so, I’m not indifferent to judgment. I just don’t think a lot about it or regard it as resolvable––or even desirable to resolve.

~~~

What interests me is the impact of the work on one’s life, on the state of waking response to being alive, on the intensity of mind generated by the experience of art, both making it and witnessing it. The kind of thinking I do making art differs from the kind of thinking I do otherwise, because it is not separate from the making. The discipline intrinsic to making art and to thinking inside that making is learned in the process itself––it’s self-informing. And, in my view, one of the interesting things about giving primacy to thinking about art in terms of principle, rather than concept, is that the thinking entrains more directly to the process of making the art generated by the principle. It speaks beyond the art question and enters the way of thinking about other questions. Principle is previous to art, previous to thinking, previous to identity, except perhaps as any one of these is thought as principle. The poetics of art thinking is inseparable from the poetics of art making.

~~~

[continues]

~~~

~~~

~~~

~~~