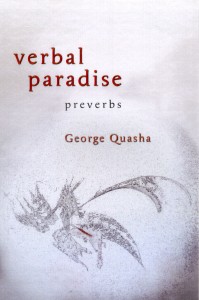

Verbal Paradise (preverbs) (2011)

~~~

~~~

~~~

This is the first book of a projected six books of preverbs,

published by Zasterle Press (editor Manuel Brito) in La Laguna (Canary Islands, Spain).

Below: the introductory prose text (pre play).

distributed and sold in the USA by SPD

~~~

Video: GQ reading in Cadmium Text Series, Kingston, New York, 2-12-11

~~~

~.~~

~~~

Responses:

~~~

“Words say too much to let you know the truth.’’ George Quasha’s torqued, enigmatic proverbs create unlikely balances among discrepant engagements. The vectors of these marvelous poems work at cross purposes, keeping each other aloft. These are sparkling aphoristic aporias for a new age in an old time. “Poetry,” says Quasha, “resists immortality with difficulty.” And also with wit and charm. Be here now, in which case immortality will take care of itself.

~~~

Charles Bernstein _———————-

~~~

~~~

Ludic, glittering dialectic, that’s the true feeling of the ongoing dance in preverbs, here now in a first volume, Verbal Paradise. The lines are all children, bright and witty children, egging each other on to say fast as they can what they don’t yet know. And we can know only by listening to them tussle. It’s the antiphonal give-and-take that makes these poems so different from other couplets, qasidas, dyads. They refuse to be ruled even by the form they propose. So reading them is an athletic conversation. And not just the poem with itself. What happens is that as I read along, I begin to talk back–in accord or grumblement—with some brave line, only to find a line or two later the poem answering my comment. The poem gets there before me. I like that.

~~~

Robert Kelly ___–____________

~~~

~~~

Verbal Paradise

~~~

preverbs

~~~

~~~

contents

~~~

~~~

pre play

~~~

this is not what you think

my past’s different from what used to be

verbal paradise is not a turn away

defining gesture

bottling up

response request

holding you at a distance

~~~

pre, a coda

~~~

~~~

~~~

~~~

pre play

~~~

There is no end to language.

~~~

That statement might speak for a big part of what drives the work of preverbs[1]. Of course the sentence is multivalent in the way it strikes the mind, which might include saying of language that “there’s no end in sight,” “there’s plenty of it,” “it doesn’t just go away,” “there’s no intrinsic end point,” “it’s unlimited in its nature….” How can one ever think of being on top of what can’t be bounded? Yet mostly we humans do keep language under locks (with or without keys) of one kind or another, and we’re not evidently comfortable when it tries to run free—really free, beyond “control.” Perhaps dolphins and whales have found a better way.

~~~

At the most complex level the principle of language limitation is constitutive within our poetics. And no doubt one could do a history of poetry and poetics purely on the basis of direct and indirect attitudes toward language and its limitations, although the evidence may not be as easy to gather as would seem.

~~~

Blake saw language like everything else as intrinsically self-regulating, a precarious self-balancing of dynamic contraries. Of course in practice language rarely appears to regulate itself. Most of what we think of as limits and limitations are extremes we go to (“mind-forg’d manacles”), forgetful of natural constraints of energetic play in mind and body. And Blake created a body of work, by no means easy to read or fully comprehend, in which reader/viewer is offered a means of engagement with the problematics of language self-limitation. It’s a process of entering the unexperienced inner workings of mind in language, one that would reflect the very nature of mind and its responsibility for life at large. Perhaps this kind of engagement is of the nature of poetry itself, at least indirectly, yet it’s not always manifest; and it’s no simple matter to discover it. Some poetry encourages a very basic and thorough inquiry into, or exploration of, what might be called language mind; this would seem related to Stevens’ “poem of the mind in the act of finding/What will suffice.”

~~~

The work of preverbs, of which this is the first book to enjoy publication, resists introductory or explanatory remarks, even as it makes them inevitable in the context of poetry. Preverbs precede themselves, so to speak, with hidden trapdoors; but this rather elusive distinction regarding a radical of composition is not like premeditation or conceptualization. One instance has to do with the relationship of preverbs to poetry in any pre-existing sense. The question “is this poetry?” has to remain open; if preverbs have a program it’s an openness regarding their own nature, especially in relation to the big consensual distinctions (poetry, even language). (Preverbially: poetry is what still exists on the other side of the distinction.) The escape-hatch approach to definition-qualification is not a defensive act by which, say, preverbs would ward off all conceptual framing or aesthetic theory (which they quite willingly play with); rather, it’s an expression of their nature to promote mind-degradable utterance. Thinking, unthinking, further thinking; saying, unsaying, further saying.[2]

~~~

In biology degrading is hardly negative; in fact, it’s positive at least in the sense of being a necessary stage of the so-called life cycle. Yet “cycling” is only one perspective on what life is doing; it’s also passing through a sort of Klein bottle wherein recycling language formulations are continuously changing in the process of sustaining linguistic life—and an attitude of: Don’t look back, old meaning might be gaining on you. Even when seeming to change levels in meaning, one’s reading, one’s vehicle, never departs from a sort of continuous single surface reality: language, the actual language that is always just now happening in front of us.

~~~

Preverbs in this sense could be pre-mind-degraded verbal action matrices—apparently accidental reconfigurations waiting to happen. (And that’s what Bucky Fuller called a “mental mouthful.”)

~~~

This approach to language might at first seem manipulative, that is, unless one considers its relation to the way language works at large—and the way that relates to (in Stevens’ felicitous phrase) the structure of reality. It must be acknowledged that this view allows for a certain independent life in language, and one can entertain this view without taking a position as to the nature of that life. One can, after all, dialogue with something of unknown existential status. Stones, mysterious objects….

~~~

Preverbs are neutral on various issues of identity, yet they are in a state of tension in the presence of certain identity acts—especially, naming things. Personally I have the sense that many things get tired of their names, particularly when they no longer really fit; they seem to be requesting liberation, which draws poetic mind to them (acknowledgments here to Bachelardian phenomenology). One of the great poetic functions working for the public good is the destabilization of naming. But this is not the place to discuss the politics of nominal reification, although it’s deeply important in the less evident processes behind preverbs. Fundamentalist approaches to language, including a naïve belief in the public meaning of words, are obviously linked (causally as well as reflectively) to the state of the world—and I think of such powerful naming as mostly bad magic.

~~~

Preverbs could in part be viewed in terms of their commitment to attracting language away from entropic verbal behavior. Language deprived of its wild loses power, grows weak, as it seems, in the immune system, and is subject to contamination and corruption. But what does it take to actually subvert the ever blackening magic that holds sway over the public mind through language? A core question, no doubt, yet let’s not try to answer it, at least not here. There are endless possible responses (and it should stay that way). In fact, it’s important at this point in preludial discourse to cop out, because any serious pretention of answering that question could betray actual power in the things said. Attempting to answer such “big questions” tends to involve belief, often hidden belief, in fixtures of order—contributors to a private fundamentalism. It’s the human thing, this survivalist’s dementia hardened into dogmata; throughout the day the mind reverts (inadvertently) to basic fundamentalist grasping at truth—something we cover up not only to others but to ourselves. It’s embarrassing, as it should be. To call attention to it blows the whistle on ontological distraction and linguistic disorientation.

~~~

Preverbs have their oblique point of origin in a long-term response to Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell.” His “Anything possible to be believed is an image of the truth” embodies a principle of self-regulation as intrinsic possibility of language itself. Anything possible to be said with the intensity of belief participates language at the level of imaginable truth. And such a realization is not the end of the discussion but the beginning.

~~~

Preverbs began, in one of its ways, to take on that possible endlessness, while remaining wary of one’s tendency to corrupt language with literalizing belief.[3] Again, it’s not just other people’s fundamentalist fearful symmetries and self-righteous animadversions but one’s own, stretched through emotional sinews and sequestered within theory and doctrine. (Coercive symmetry and self-serving righteousness are about as close as I get to a sense of sin, among the umpteen slipperiest sins.) Language is the memory bank of all these tendencies. Blake preferred the Daughters of Inspiration to the Daughters of Memory because the latter held language to its limitations, yet in reality one stands at the limen between them, as Blake’s work persistently engaged that dividing line with oscillatory intensity.

~~~

Preverbs also stand at the lintel of self and other and listen in on the ongoing conversation. In that focus they perform a sort of kledomantic gathering of stray language according to a singularity-centered principle of organization. But that process is not random, as might sometimes seem in casual reading. It’s less like a chance operation than, say, dowsing—with a soft grip on the talking stick. One moves with exacting ambivalence according to certain spirited attractions (with often minimal understanding in play). Robert Duncan was for me one of the initiators in this view, particularly in statements like this one from The HD Book, Chapter Two, 1969:

~~~

In Cocteau’s film Orpheus the guardian angel Heurtebise tells Orpheus not to try to understand but to follow. It is a law in the reading of poetry that is a law too in the writing. Unless we follow, unless we follow thru the work to be done, there is no other way of understanding. Participation is all.

~~~

My interest in axiality is in part the wish to align with a basic principle at work inside accurate following. The way in which one tracks the impulse, the release into a sudden inner curve, a pulse as much as a rhythm—all point to a movement within language of its own accord.[4] In fact, there are no necessary patterning tendencies, but there are endless optional ones; these show up when compulsive and otherwise dominant patterning forces are loosened, spaced.

~~~

From one view, the axial is the freedom of conscious things—intentional entities—to be more than they appear, more than we experience at once, more than we know how to know we can know. Poetics, in this sense, is self-observation as integral to the exercise of the principle itself—a life-sustaining intrinsic variable. And this puts poetics on the plane of responsible practice beyond specialization (poetry, literature) as consequential acts of mind with possible evolutionary force.

~~~

Yet no sooner do we elevate a domain and reify its importance than the mind protective of its freedom to think pulls back. It’s so tricky to specify a domain of sustained singularity—of the state generative of what recreates itself beyond precedent, of what is continuingly pre…. Baudelaire characterized a quality of mind that he associated with philosopher: “The man who trips would be the last to laugh at his own fall, unless he happened to be a philosopher, one who had acquired, by habit, the power of rapid self-division and thus of witnessing the phenomena of his own ego as a disinterested spectator.” This double-visioned ability to be of two (or multiple) minds—a state of intentional liminality, of me/not me, indeed of never just me/never not at all me—creates a gap in identity security, and startled access to one’s further nature (Olson’s inspired phrase).

~~~

In “On the Essence of Laughter” (1855), Baudelaire explores laughter—”an involuntary spasm, comparable to a sneeze”—as state of singularity that reaches a higher intensity in the “grotesque”[5]—the utterly original articulation engaging scarcely exercised faculties. He contrasts the ordinary (“significative”) comic with the absolute comic, “which comes much closer to nature, emerging as a unity that calls for the intuition to grasp it.” Closer to nature! Because nature itself, up close, very close, sheds recognition and arouses sheer configuration. It calls for a “science of imaginal solutions” (Jarry’s ‘pataphysics) based “on the truth of contradictions and exceptions” (Queneau), since, following Jarry, ultimately there are no reliable laws, only exceptions. The natural world is always already a separate reality, yet accessible by way of a work of singularity. And in what tone of voice does it speak to release its hilaritas of the dark and actual soil?

~~~

The lonely preverb emerges from its own instance, and seems to find its way out back. It often comes in a flash, and always subject to further flashing/fleshing—like the mind impulse we can call sudden thought, at times, brain squall. It has to be written as it comes, or else it goes, a bumblebee in the foreground instantly lost in the farground. Once written it can go solo or, if it sticks around, take on refugee status, subject to communitarian induction by precise attraction. But I resist the impulse to “construct” poems out of these unitaries. Rather, an axial complex takes place over time. Lines find each other like stones.[6] They co-configure, and over years, with a certain avid patience, they re-co-configure. They come together in event-structurings, rather like encampments of entities at large, learning to live together in ways that mean, where meaning is matrix. According to the axial principle: like attracts like and unlike alike. Non-symbolizing entities come into relation from unexampled streamings and crossings. And at a certain point they abide. Then the stories begin.

~~~

~~~

A NOTE ON DEFINITION

~~~

The standard definition of preverb indicates a prefix or particle preceding the root or stem of a verb, such as for- in forget. But my usage is neologistic, and in fact I was unaware of the linguistic usage for many months after the work began over a decade ago. However, that usage is interesting and sometimes relevant, especially in an extended application in which, say, the pre- of preverb is itself a preverb, creating the possibility of an unknown and still unused verb, to preverb. (This very possibility further axializes—makes more variable—both pre and verb, which event the present work celebrates.) The extended application also makes inevitable notions like “the preverb of the preverb.” NB: preverbs can be singular or plural: “the preverbs” or just “preverbs” (the whole project), or indeed “a preverbs” (a named unit, that is, a poem or, alternatively, poem–complex or preverb complex). Note too: “a preverb” can mean either a single line or a “whole” poem. The distinction preverb is in this and many other ways axial. A name that is performative of its kind resists fixity and is transdefinitional (axial). And whatever is true of the smallest unit (a singularity) is necessarily true, at the level of possibility, of the whole (a field of singularity).

~~~

~~~

notes

~~~

[1] See A Note on Definition at the end of pre play.

~~~

[2] I consider this the real meaning of apophasis (literally “speaking away”), rather than the more limited customary sense of either a rhetorical device of apparent denial, as used in literature and oratory, or logical reasoning/argument by denial, as in the designation “negative theology.” Happily some have gone far beyond the unfortunate claim of programmatic negation in, say, Meister Eckhart or Ibn ‘Arabi, especially Michael Sells in his use of the term “unsaying” (see his great work Mystical Languages of Unsaying [University of Chicago Press, 1994]).

~~~

[3] Of course one must acknowledge the relevance of deconstruction here, yet quickly discriminating a less aggressive approach by way of the principle of axiality.

~~~

[4] I would avoid here association with aleatorics as with automaticity, particularly in the way Surrealist practices have been construed, which is a complex subject about which I’m not aware of any satisfying discussion. The Unconscious, Freudianism, Jungianism conceived as definites—up for grabs.

~~~

[5] Instantaneity of the breach: “There is but one criterion of the grotesque, and that is laughter—immediate laughter. Whereas with the significative [ordinary] comic it is quite permissible to laugh a moment late….” The primitive startle that jolts the laugh reflex may not yet have known humor, but itself be messenger of an unknown humor.

~~~

[6] This statement is not basically metaphoric; it approaches a special literal status when registered in the context of work presented in my Axial Stones: An Art of Precarious Balance (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2006), which includes preverbs.

~~~

~~~

~~~

.